Electric vehicle ‘charging deserts’ plague Georgia, nation

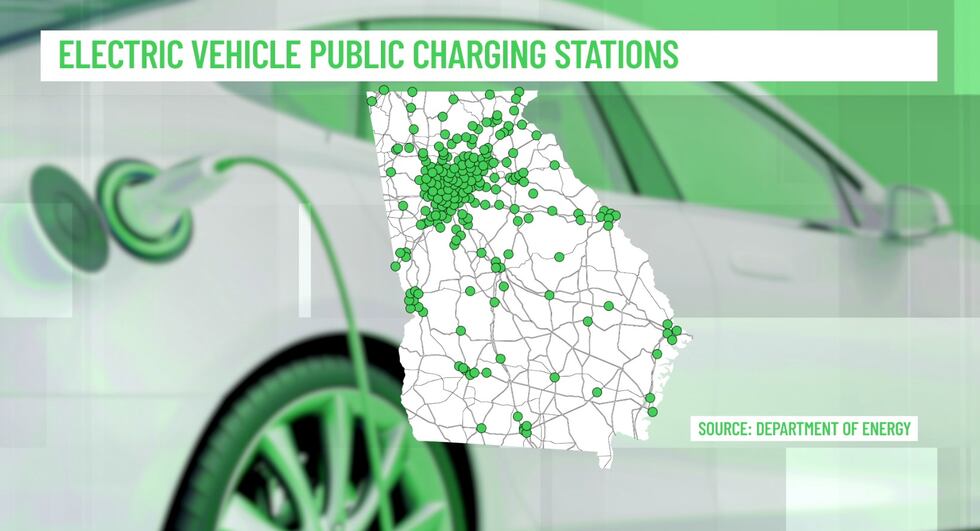

According to the Department of Energy, there are 1,600 public charging stations in Georgia with 4,000 charging ports.

ATLANTA, Ga. (Atlanta News First) - There’s a massive push to get more electric vehicles on the road, with President Joe Biden’s istration setting the goal of having EVs for half of all new car sales by 2030.

But as new EV drivers the millions already on the hunt for charging stations, they may wind up stranded in “charging deserts.”

Just like it sounds, a “charging desert” is an area where charging stations – where drivers plug in and re-charge – are scarce or even nonexistent.

Public charging stations are concentrated mostly in urban areas, with shortages plague many rural areas.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Georgia has 1,600 public charging stations with 4,000 charging ports.

A closer look at Georgia’s public charging stations shows that state aligns with national statistics. The majority of chargers are in major cities — Atlanta, Augusta, Macon, Columbus and Albany — while the rural areas have fewer or none at all.

Justin McCormick knows the struggle all too well. He’s got an electric vehicle he’s in love with, in part because of how its technology aids him with planning out long trips.

“I know exactly when I’m going to get there. I know how long I have to stop, the charge, everything,” McCormick said.

But his plan for a trip from Austin, Texas, to Arkansas to see his family went south quickly once he got north of Dallas and headed into Oklahoma. McCormick’s car, which can usually find charging stations at the push of a button, suddenly couldn’t locate any options as his charge dwindled.

“All of a sudden, the battery was like, ‘Just kidding, we can’t make it anymore’,’” he said.

McCormick found himself in what’s called a “charging desert.” Outside the east and west coasts, these deserts are fairly common, with federal data on charging stations examined by InvestigateTV showing EV infrastructure lacking in many places, especially middle America.

The lack of charging options in many places creates what EV drivers call “range anxiety,” with many concerned their cars won’t have the charging capacity to make it through long trips. Concerns about the problem are echoed all over social media with people from across the nation calling out a lack of publicly accessible charges.

“That really creates a lot of barriers that I think that people don’t realize,” McCormick said.

National data from June from the Department of Energy analyzed by InvestigateTV shows there are more than 53,000 public charging stations for electric vehicles across the U.S., often located near convenience stores, parking garages, or universities.

Data shows California, New York and Florida are the top three states when it comes to the most available public chargers, with thousands located in each.

However, InvestigateTV discovered there are five states — Alaska, Montana, South Dakota, North Dakota and Wyoming — with fewer than 100 stations each.

The federal data shows less than 15% of all public charging stations nationwide have DC Fast chargers. Those are the quickest type of charging ports that can typically charge 200 miles in a matter of minutes. Most stations are Level 2, where charging could take hours.

Even when public chargers can be located, InvestigateTV’s analysis discovered many places may have restrictions that limit hours of operation, put caps on charging time, or require you to bring your own cord, creating other problems for EV drivers.

“There is much more that needs to be done to strengthen the network,” said U.S. Rep. Abigail Spanberger (D-Virginia).

Work to bolster the EV charging network and eliminate deserts is already getting a boost from the federal government, with the bipartisan Infrastructure Law channeling $5 billion over five years to the effort in hopes of building a national network of 500,000 chargers in the next seven years.

But with much of the focus on EVs so far centered on big cities and suburbs, Spanberger is fighting to make sure charger funding also makes its way to rural areas, saying it would be “catastrophic” if they were left behind.

The lawmaker, whose district includes parts of rural central Virginia, has introduced legislation designed to fund EV charging infrastructure specifically for farmers. She said rural areas will feel the pain well into the future if they’re not prioritized for charging stations, pointing out that small towns and counties would greatly benefit from the revenue created when chargers become destination points for drivers.

“They’re not just having to hug the interstate because they think that’s where they’re going to be able to find the charging stations,” Spanberger said. “Those can be major drivers of tourism to rural and agricultural communities.”

Concerns about the need to fund EV charging stations in rural areas are shared by stakeholders across the country, including environmental groups pushing to expand green infrastructure.

Emily Wirzba handles federal affairs for the Environmental Defense Fund. “We have a real opportunity right now to make sure that rural communities aren’t left behind,” Wirzba said. “That’s not a foregone conclusion.”

Wirzba emphasized that stakeholders have to get involved in the process now because every state in the country is getting a piece of the $5 billion designated for EV infrastructure, and every state must submit specific plans outlining how they’ll spend it year by year.

“It’s a really pivotal moment right now because there’s a chance to course correct. We can give to let the government know the funding is working,” she said.

InvestigateTV analyzed those state plans for spending the federal funding, discovering the primary work is focused on building out so-called “Alternative Fuel Corridors,” or AFCs, along some of the nation’s busiest highways. That effort will put fast EV charging stations every 50 miles, no more than a mile off the interstate.

After that, Wirzba said states have more wiggle room to decide where stations could go off the beaten path.

“It’s up to their state department of transportation to have conversations across the state to figure out where they need charging the most,” Wirzba said. “The conversation is really geared toward making it work for the local community.”

Underserved and rural communities will also get a boost from another round of funding recently announced by the Biden istration. That grant program will funnel an additional $2.5 billion to help build out EV infrastructure, with those specific areas getting approximately half of the funding.

Justin McCormick is pictured with the electric vehicle he purchased last year in Austin, Texas (Justin McCormick)

Drivers like McCormick know first-hand how much the funding, and the charging options it will create, is needed. He got help from customer from his EV manufacturer and was guided to a gas station with a plug in he could use to boost his charge.

Encountering a charging desert didn’t change McCormick’s mind about owning an electric vehicle, but he said it is impacting his family’s decisions about purchasing another one, especially with long trips home on his mind.

“If there were options along the way, we would probably both have electric vehicles,” McCormick said.

If there’s something you would like Atlanta News First investigative reporter Rachel Polansky to dig into, email her at [email protected].

Copyright 2023 WANF. All rights reserved.